Catholics in China: Back to the Underground

by Patrick E. Tyler

Reprint from the New York Times, Front Page

January 26, 1997

![]()

Except for one-time personal use, no part of any New York Times material may be reproduced by any mechanical, photographic, electronic process, or in the form of photographic recording, nor may it be stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or otherwise copied for public or private use without written permission of the New York Times permissions department.

COPYRIGHT © By The New York Times Company. Reprinted by permission.

![]()

YUJIA, China - It was the day before Easter 1995, and they came by bicycle and horse cart and on foot, thousands of Roman Catholics from the underground church, and they climbed up into the pine forest on what is called Yujia Mountain, though it is scarcely a hill.

There, they chased away several troops who had never intruded in their place of worship before and who insisted that they were conducting training exercises essential to the national defense.

Then, the Catholics, more than 10,000 of them, began to pray. They filled the pine forest here with their song. The leaders set up a platform from which they read out the Scriptures, and the people danced and reveled in their community all the way up to the potent spiritual moment of the Easter sunrise.

Today, the leaders are in jail, charged with interfering with the military training exercise. Others are on the run. And a visit to this onetime hotbed of religious fervor is a somber thing.

Over the last two years, Yujia and dozens of other centers of underground religious activity in China have been the target of a crackdown by the Communist Party authorities, who see religion as a vehicle for political organization, dissent or outright opposition to the party's rule.

The harsh treatment of Catholics in China dates to the 1950's, when Mao Zedong's Communists expelled the last papal representative and set up the Catholic Patriotic Association, an official church under Communist control that was more a tool of persecution than propagation. Driven underground, the underground, the unofficial Catholic Church received a broad mandate from the Vatican to persevere as best it could by ordaining its own bishops and adapting the liturgy to local conditions. When China emerged from the Maoist period, some churches reopened and religious toleration expanded during the 1980's with Beijing seeking to lure more religious believers into the Government-supervised religious organizations. But without a reconciliation with the Vatican, millions of Catholics remain underground, where some local governments have tolerated them. Still, they are subject to periodic assaults ordered by central authorities.

The first clues that repression hangs as heavy as the winter haze over this remote village in Jiangxi province, in southern China, are the wall slogans that the police have painted in recent weeks:

"Catholics are not allowed to engage in illegal propagation activities."

"Catholics are not allowed to go to other areas and establish networks."

"Get rid of all illegal religious gatherings and activities."

To enter this village as a stranger is to set off alarm bells. The villagers know that strangers have been sent to live here as spies against their neighbors, and to report to the Public Security police station a mile away any violation of the harsh rules that have been laid down.

"The Government is afraid that if we practice our religion, that this will be harmful to security," Zou Chunxiang, 56, said as her neighbors and a few stray chickens crowded around her on the dirt floor of her unheated house. "The Government is afraid we will conspire with foreign countries and overthrow the state."

Some of her neighbors giggle at such a prospect, but Ms Zou is silent because all of the men in her family are either in jail or on the run for practicing their faith.

The new wave of religious repression in China seems in largest measure the product of President Jiang Zemin's policy to shore up the "socialist spiritual civilization" of a population that pays as little attention as it can to central authority.

Beginning in 1994, Mr. Jiang began to preach to the party faithful that "social stability" is of paramount importance to the party's survival and therefore must be preserved at all costs, even if that means slowing the pace of Deng Xiaoping's economic reforms, re-imposing price controls when they are needed and crushing political and religious groups whose activities could serve a vehicle to challenge the Government's legitimacy.

To bend religion to the interests of the state, Communist Party strategists have devised plans to ban house churches, arrest religious leaders, register church members, and use military means if necessary to block their unregistered gathering places.

The most recent phase of the crackdown began here in November, when the police started arresting underground organizers to prevent them from holding a Christmas celebration on this modest mountain, which is at the end of a 20-mile dirt road from Chongren, the nearest county seat. Up until 1995, Catholics from all parts of Jiangxi traveled here four times a year to pray.

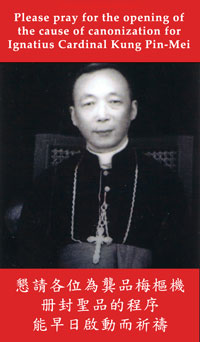

The Cardinal Kung Foundation in Stamford, Conn, an advocacy group named for the Chinese prelate Ignatius Cardinal Kung, whose Chinese name is Gong Pinmei and who spent 32 years in prison before his release in 1988, estimates that 80 people were detained in this area.

A copy of an action plan to "destroy the organization of the Catholic underground forces" around Yujia was obtained by local Catholics and smuggled out of China. It was published by the foundation this month.

Local Catholics said recently that many of their number were still in detention and that those released had been forced to pay stiff fines to the police, equal to half a year's income.

"Every Sunday in the village, we used to gather in one house to pray, but now we can's even do that," said the 26-year-old farmer in Yujia. He has built an altar of tile and brick in his home and adorned it with renderings of the Last Supper, the Crucifixion and the Ascension.

The great religious revival that began sweeping china two decades ago is coming under greater assault as a new generation of Communist Party leaders in Beijing fear the growth of its moral and spiritual power as the official creed of Marxism-Leninism declines.

"Nobody believes in Communism as a transcendent, quasi-religious ideology anymore," said Richard Madsen, a sociologist at the University of California at San Diego who has completed a study of the underground Catholic Church in China.

"In the past," he said, "many people did believe, and it motivated them to hard work and sometimes great self-sacrifice that gave a kind of moral legitimacy to the Communist state because it was a moral project to build the state - a religious project ultimately."

Now, he added, there is a "loss of meaning" and a "spiritual vacuum" for millions of Chinese who are turning to religion.

"In the past," he said, "many people did believe, and it motivated them to hard work and sometimes great self-sacrifice that gave a kind of moral legitimacy to the Communist state because it was a moral project to build the state - a religious project ultimately."

By some estimates, more people have joined Christian groups in recent years than have joined the Communist Party. Today, there are about 53 million party members, but a February 1996 internal Communist party document estimated that there were perhaps 70 million religious believers in China.

When the Communists took power in 1949, there were only one million Protestants in the country. Today there are an estimated 20 million, though the publicly acknowledged figure remains at 6.5 million.

Government statistics say there are four million Catholics in China, but church organizations and Western academics say 8 million to 10 million is a more reliable estimate.

Whatever the number, it is growing, as is the threat that Communist Party leaders perceive.

"I think there is a paranoia about the role the church played in Eastern Europe," said Mickey Spiegel, a research associate at Human Rights Watch in New York, referring to the support that the Catholic Church gave to the collapse of Communism in Poland and elsewhere.

Last spring, thousands of paramilitary police supported by armored car units and helicopters swept into the tiny enclave of Donglu in Hebei Province and destroyed a Marian shrine to which more that 100,000 underground Catholics had made pilgrimages the previous year.

The soldiers destroyed the shrine, they confiscated the statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and they arrested two bishops," said Joseph Kung, president of the Kung Foundation and a nephew of the Cardinal.

Among those arrested was Bishop Su Zhimin, of Baoding, who joins Bishops Thomas Zeng Jingmu, 75, Bishop Joannes Han Dingsiang and the Rev. Charles Guo in jail or labor camps.

The Chinese authorities have tried to keep foreign journalists from covering the current crackdown. A correspondent for The Washington Post was detained in 1995 from traveling to Donglu to witness an outdoor Mass for 10,000. He was later released.

This month the local police briefly detained this correspondent during a visit to Yujia, and confiscated all notes of interviews and a roll of film.

The crackdown on religion, particularly the underground Catholic Church, comes at a time when Beijing is locked in a contest with Taiwan to win the Vatican's diplomatic recognition.

Beijing's success last year in persuading South Africa to drop its recognition of Taiwan has made the Vatican prize all the more important in Beijing's campaign to isolate Taiwan internationally.

Pope John Paul II has said he would like to visit China, but a debate reportedly rages in the Vatican between those who want the Pope to stand firm until the repression ends in China and those who believe he could make a more compelling case for the plight of Catholics by making a visit.

John T. Kamn, an American who has combined a business consultancy in China with human rights advocacy, has warned the Chinese, that reconciliation with the Vatican, on which Beijing is said to be keen, will be "very, very difficult" if the "bishops and priests and laity of one community are continually subjected to beatings, to arbitrary detention" and "if their places of worship, their holy shrines are destroyed and their celebrations banned."