Review & Outlook

A Man for All Seasons

The Wall Street Journal

March 17, 2000

![]()

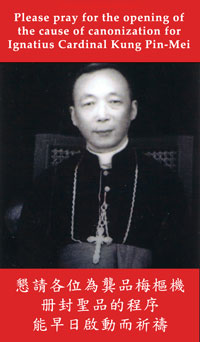

The Gospel of Mark tells us that a prophet is without honor in his own land. What a fitting epitaph for Ignatius Kung Pinmei, the bishop of Shanghai, who died Sunday, in exile in the U.S. of stomach cancer. In Rome, Pope John Paul II lauded the cardinal's "heroic fidelity," while in Beijing an official would say only that it would be left to history to treat the subject.

Of course, even the densest Party cadre appreciated that history is likely to treat Cardinal Kung far more favorably than the Communist government of China ever did. Ordained a bishop just days after a triumphant Mao had proclaimed his People's Republic, this unassuming cleric put the lie to the gospel certitude of the new Communist government that Christianity would wither on the vine once the foreign missionaries were expelled. Ignatius Kung did not wither. Brought before a mob to confess his "crimes" after his arrest in 1955, the priest stepped up to the microphone and announced, "Long live Christ the King! Long lived the Pope!"

In refusing to submit to Party demands, Cardinal Kung drew an old distinction. Caesar may rightly claim many things from his subjects. But when he claims hegemony over the soul, he has gone too far. The price of drawing that distinction was three decades in jail, the bulk of which was spent without books and without letters to and from friends or family.

In the thick of the Cold War in 1979, at a time when the world's eyes were focused on Moscow, Pope John Paul named a cardinal in pectore (literally, "in my breast"), which means that his identity would be kept secret. The assumption was that the secret Cardinal was somewhere inside the Soviet Union. In 1985, China finally released Bishop Kung, without either the bishop or the Chinese government knowing the truth. In 1991, the Pope told Bishop Kung the news shortly before he told the world: The "catacomb cardinal" was in fact Cardinal Kung, elevated to the red hat at a time when he was still rotting away in a Chinese dungeon.

Four centuries after a brilliant Italian Jesuit named Matteo Ricci sought to cultivate a Christianity that was authentically Chinese, one of the finest fruits of those labors, Cardinal Kung, found himself deemed such a threat precisely because he was Chinese. Like Chinese holy men of many persuasions, to taste freedom this Roman Catholic cardinal had to leave China. No doubt his passing will be the occasion for musings about trade and human rights, especially in the U.S., where some have long invoked the ailing cardinal's name for causes and positions unlikely to have been his own.

Inside China, the cardinal's willingness to suffer and his refusal to bend inspired countless others in similar circumstances. Outside China, his story reminds us that religious freedom remains an excellent test case for measuring regimes. As the cardinal realized early on, governments that do not recognize a man's autonomy over his own soul are not likely to recognize his autonomy over anything else.