Beware Communists Bearing Gifts

by Michael Sheridan

The Tablet, The Catholic newsweekly of London

August 6, 2005

![]()

Recent indications of a thaw in relations between the Church and Communist China have been welcomed. But they should not be trumpeted too loudly while Beijing uses the Vatican in its fight over Taiwan

![]()

As you board the ferry at the Fragrant Harbour here in Hong Kong you may be greeted by devotees of Falun Gong, a meditation group, and as your boat plies its crossing, cathedrals, temples and mosques arise like pinpricks of conscience amid the skyscrapers devoted to Mammon.

The former British colony is the only place in the entire Chinese land mass, from the deserts of Tartary to the rushing torrent of the Tumen river on the North Korean border, where religion is free.

Bishop Joseph Zen, the leader of Hong Kong's Catholics, speaks as fearlessly as he thinks prudent. Hong Kong's chief executive, Donald Tsang, attends daily Mass. The ranks of government and commerce are salted with the products of diocesan schools and teaching orders, a legacy of their flight from Communist China after 1949.

At a time when Beijing has made what could be interpreted as conciliatory gestures to the Vatican, and there is talk of the Vatican establishing diplomatic ties with Beijing for the first time since the revolution, abandoning the island of Taiwan to do so, a visit to Hong Kong's enclave of freedom should give the silkiest diplomat pause for thought.

Whenever I see the symbols of religion here – the flourishing churches, the chanting Tibetan monks, the evangelists working the streets – I am haunted by the childhood memory of a soft voice saying the Latin liturgy. It is the voice of Father Andrew Kavanagh, and I am transported back four decades to a cold church in north London's Mill Hill, on my knees as the solitary altar server saying responses at the seven o'clock Mass on mornings in Lent, with my mother sitting in the front pew. Father Kavanagh, we children heard older parishioners whisper, had seen and suffered much at Communist hands as a Vincentian missionary in China. So, too, they said, had his brother, who was also a priest. Of course, he never spoke of it to us – that generation didn't – but there was a weary gentleness about the old priest that I now recognise, after years of reporting on conflict, as a sign of profound injury.

Then his voice recedes and, just in case readers think that this is another article about Catholic nostalgia, I am brought bang up to date with the latest communications from the Cardinal Kung Foundation, whose contents should be thundered out from every pulpit.

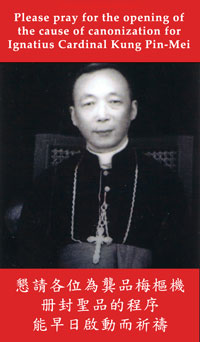

The foundation exists to spread news of the underground Catholic Church in China today and to remind us of the fidelity of Cardinal Ignatius Kung, who endured 32 years of imprisonment and ill-treatment before his death in exile five years ago, aged 98-plus. Here are some examples, not from Father Kavanagh's era, but from 2005 in Hebei province, a poor rural part of central China.

On 31 March, the police arrested Bishop Yao Liang, who is in his early eighties. He was under pressure to sever ties with the Pope but had refused to do so. On 1 April, Father Wang Jinling, another octogenarian, was arrested. At the same time, state security agents intensified their surveillance of Bishop Hao Jingli, who is 89, and Bishop Jia Zhiguo, who is aged 70, and who are the underground Catholic bishops of Xiwanzi and Zhengding respectively.

These moves came as word reached millions of Chinese Catholics that Pope John Paul II lay dying. The Pope had created Ignatius Kung a cardinal in pectore (secretly) in 1979 – the appointment was revealed only in 1991 – and his canonisation of 120 Chinese saints in 2000 had inspired even greater loyalty among believers. On news of his death on the evening of 2 April, Masses and novenas were said for him all over Hebei province, usually in homes where the faithful could gather in secret.

"As a rule there is no open public church in the underground Church in China, with the exception of very, very few in small villages," said Joseph Kung, the cardinal's nephew, who runs the Kung Foundation.

To grasp the problem confronting the Vatican in its dealings with China, it is helpful to understand the timing of what happened next. Formally, the Chinese Government expressed its condolences, spoke of its desire to improve relations with the Vatican and welcomed the election of Benedict XVI. Its newspapers reported the events as if Catholics were another exotic minority group under the protection of a benevolent state. Foreign TV networks were allowed to film worshippers paying their respects at government-sanctioned churches.

Far away in Hebei province, the situation was very different. The security forces stopped any demonstrations of mourning. The clampdown was as efficient as that which crushed the meditators of Falun Gong when they were deemed to pose a threat to the state. Eventually, in late April, the 24-hour surveillance of Bishop Jia was relaxed. According to the Kung Foundation, seven priests from parishes in his diocese, Zhengding, joined a retreat under his guidance.

On 27 April, all seven were arrested by officers of the religious bureau backed up by dozens of police. The Bishop was warned "not to initiate any religious activities" and the priests were sent off to the local security bureaux in their parishes.

In the months that followed, the Chinese Government gave numerous signs of its wish to mend fences with Rome. Bishop Zen of Hong Kong was welcomed with courtesy on a visit to the mainland. Informal contacts multiplied through such avenues as the community of Sant'Egidio in Rome. Archbishop Giovanni Lajolo, the Vatican's Secretary for Relations with States, said recently that the establishment of diplomatic relations had been under consideration for some time. Other Vatican officials hinted that the Apostolic Nunciature could be transferred from Taipei to Beijing, even before all the details were settled.

Latest evidence of detente was the consecration of Bishop Joseph Xing of Shanghai, whose elevation has apparently come about with the approval of both Beijing and Rome, even though the Chinese have not explicitly acknowledged the Pope's right to appoint him and the Holy See did not push the point.

Yet again there was a stark contrast between the regime's propaganda overtures and the deeds of its agents in Hebei province. On the afternoon of 4 July, says the Foundation, Bishop Jia was arrested for the sixth time by a pair of government officials who took him away to an unknown location. In one of those exquisite details of Communist method that has the ring of truth about it, they are said to have telephoned in advance to order him to tell the people that he was being taken to visit a doctor. He was not ill. The bishop was released without explanation after four days.

Bishop Jia is a peaceful churchman who suffered 20 years in prison and has lived under close watch ever since. He helps to care for 100 handicapped orphans at his residence. He ought to be as well known as Nelson Mandela or Aung San Suu Kyi. Remorseless, capricious and petty, the persecution of the bishop – there is, frankly, no other word for it – exhibits every characteristic of the modern mandarins.

It would be tempting to interpret this behaviour as a subtle Chinese policy of blandishment and threat, the classic twin-track cold war formula that often yielded a diplomatic compromise. Archbishop Lajolo has used the words "good will and a spirit of friendship" towards China, an approach that stands in stark contrast to that of the Chinese Communist Party's new leader, Hu Jintao. He made it clear in a series of secret speeches leaked to the Washington Post that he stands for authoritarianism and against freedom, praising North Korea and Cuba for their political systems.

The Catholic Church could yet prove useful. Hu Jintao's priority is to undermine the democratic government on Taiwan and ultimately to reunite it with China under Communist rule. Recognition by the Vatican of the Government in Beijing is a prize that would strengthen that regime's questionable legitimacy and weaken its foes.

In its desire for control, the Communist Party cannot tolerate any alternative source of authority. Its entire political and diplomatic posture, whether towards Rome, Taiwan, Tibet or its internal enemies, must be understood on this basis. Recently a Chinese general even threatened the Americans with nuclear war over Taiwan. For this regime, the issue is existential. All the evidence is that it cannot allow genuine compromise, still less creative ambiguity, over matters of sovereignty.

Like the secular martyrs of Tiananmen Square, and like the thousands of bishops, priests and faithful Catholics thrown into labour camps or killed since 1949, Cardinal Kung is still regarded as a criminal in China. His offence was to keep alive an underground Church that may have as many as 12 million adherents, compared with the four million known to worship in officially sanctioned Catholic churches.

Indeed it was none other than Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger who congratulated Cardinal Kung in 1999 on the seventieth anniversary of his priesthood with these words: "You have followed the example of Christ the Good Shepherd and even in the face of great suffering have not ceased to proclaim the truth of the Gospel by your words and example."

I do hope that, from their undoubted places in heaven, Cardinal Kung and Father Kavanagh will inspire the Pope and his diplomats to realise that the Vatican can afford to wait.

Michael Sheridan worked for Reuters and The Independent as a correspondent in Rome and has been Far East Correspondent of The Sunday Times since 1996.