Church Militant

Communist Party dossiers reveal the methods that dismantled a flourishing Catholic community.

by Thomas J. Craughwell

National Catholic Register

May 8, 2012

![]()

This article is reprinted here with the permission of The NCR

![]()

No China scholar wants to answer a knock on the door and find Chinese government officials standing at his doorstep. Yet, in 2006, that is what happened to Jesuit Father Paul Mariani. He had traveled to China to research how the Communist Party crushed the Catholic Church in Shanghai, one of the most dynamic Catholic communities in the country.

No China scholar wants to answer a knock on the door and find Chinese government officials standing at his doorstep. Yet, in 2006, that is what happened to Jesuit Father Paul Mariani. He had traveled to China to research how the Communist Party crushed the Catholic Church in Shanghai, one of the most dynamic Catholic communities in the country.

While working in the Shanghai Municipal Archives, Father Mariani discovered newly de-classified dossiers that detailed the party's campaign against Catholics and how the communists dismantled the Church in Shanghai.

Realizing that he had a real treasure in his hands, he asked the archivists if he could have copies of the material; incredibly, they said, "Yes."

"Then things got interesting," Father Mariani recalled in a recent interview. "A month after I was given copies of this material, some people from the archives visited me. They told me they had made a mistake: They should not have released the material; they wanted everything back. Why this sudden change in policy? I will never know. Luckily, I had earlier safeguarded my most crucial documents. It is this critical material that is now in the book."

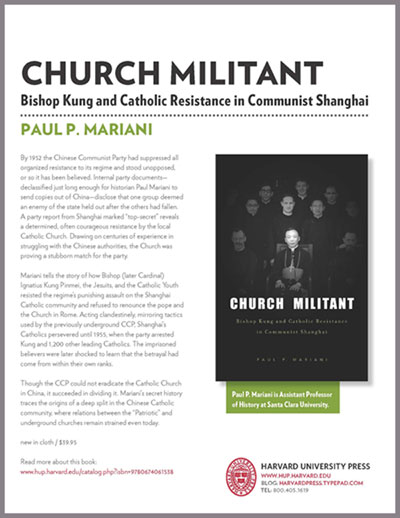

"The book" is Church Militant: Bishop Kung and the Catholic Resistance in Communist Shanghai (Harvard University Press, 2011). By the time Mao Zedong and the Chinese Communist Party took over China in 1949, Catholic missionaries had been working in the Shanghai region for 350 years. In fact, some Franciscan missions to other parts of China went back over 600 years.

From the beginning, Catholicism flourished in Shanghai: By 1703, the city's growing Catholic population worshipped in two churches and 30 chapels staffed by Jesuit priests. A 1950 city map Father Mariani includes in his book reveals that there were at least eight major parish churches in central Shanghai alone, including St. Francis Xavier Cathedral, and dozens of chapels. There was also a minor seminary and a major seminary, the Jesuit School of Theology, a Catholic university for men, a Catholic college for women, a Catholic teachers' college, four Catholic high schools, two Catholic medical facilities, four convents and two Catholic orphanages. In the suburbs, there was the massive pilgrimage site to the Blessed Mother, Sheshan Basilica.

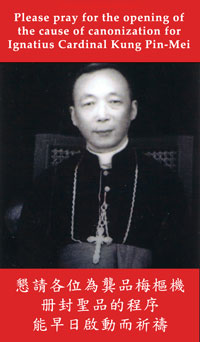

The leader of the Church in Shanghai was Bishop Ignatius Kung (1901-2000), whose family had been Catholic for five generations. When he was consecrated bishop in 1949, Kung expected that he would meet martyrdom at the hands of the communists, and his suspicions were accurate. The Chinese Communist Party was aggressively atheistic and targeted all religions in the country for destruction. The Catholic Church, with its many missionaries from America and Europe and its ties to Rome and the entire universal Church, gave the communists the ammunition they wanted to depict Catholics as counterrevolutionaries, spies and the tools of foreign imperialists.

Kung began his administration of the diocese by issuing a pastoral letter that called for greater zeal among all the Catholic faithful of Shanghai. He encouraged active cooperation between the clergy and the laity, an intense program of evangelization to non-Catholic family, friends and neighbors, new fervor in attending Mass, attending benediction of the Blessed Sacrament, participating in pilgrimages and praying the Rosary. He also called for more vocations to the priesthood and the religious life. Bishop Kung's goal was to strengthen the roots of the Catholic faithful of Shanghai, so they would be prepared for the assault he knew was coming.

Bishop Kung also called upon the members of the Legion of Mary and the diocese's various Marian sodalities to increase their own faith and that of their fellow Catholics through fervent prayer, especially to the Blessed Mother, and to begin an intense catechetical program to deepen their understanding of Catholic doctrine. Catholic youth especially responded to the bishop's call, and it wasn't long before catechetical groups could be found in virtually every school in Shanghai, Catholic and public, from the elementary grades all the way up to the university level.

The communists responded by denouncing the Legion of Mary and the sodalities as organizations that poisoned the minds of the young with "anti-Soviet, anti-communist and anti-people thought."

Shanghai's Catholic youth organizations were led by a Jesuit priest, Father Beda Chang. Over the course of his career, he had been principal of Shanghai's prestigious St. Ignatius High School, dean of Aurora University, director of the Bureau of Sinology and consultor to the superior of the Jesuit mission. In dealing with the communists, he sought a middle way, encouraging Catholic youth to remain faithful to the Church and loyal to China, insofar as the government did not try to compromise their Catholic principles.

Father Chang's middle way broke down when the Communist Party insisted that the Catholics of China must break their ties with the universal Church and accept that the party would have sole authority over the Church in China. The communists' goal was to place Chinese Catholics under the direction of a puppet church that obeyed and supported the party in all things. In a meeting between party officials and the heads of all Catholic schools in Shanghai, the Catholics protested that they could not grant to any government an authority it did not possess; they refused to go into schism. In response, the government began to confiscate Catholic schools, including the Jesuit flagship, St. Ignatius High School.

On Aug. 9, 1951, police entered the Jesuit residence and arrested Father Chang. They held him for four months in the Ward Road Jail, where he was subjected to starvation, sleep deprivation and repeated interrogation sessions that stretched on for hours, often from dusk until dawn. The abuse was slowly killing Father Chang. Toward the end, his fellow prisoners heard him repeating, "Jesus, Mary and Joseph, help me." He fell into a coma and died in the prison hospital.

The cruel death of Father Chang outraged Shanghai's Catholics. Thousands gathered in the streets to demand Father Chang's body. Male students wore black armbands, while female students wore in their hair a white knot, the traditional Chinese emblem of mourning. Rather than offering a funeral Mass, some priests celebrated the Mass of the Holy Cross, wearing red vestments, the liturgical color for a martyr.

Father Mariani believes that Father Chang is a likely candidate for canonization. "I believe his case parallels that of St. Maximilian Kolbe," Father Mariani said. "Kolbe had a long history of educating and animating the Catholic community before his imprisonment and death in Auschwitz. Similarly, Chang is not only known for his steadfast faith in the face of starvation and exposure in Shanghai's Ward Road Jail. He already had a sterling reputation among the Catholic faithful."

Beginning of the End

The death of Father Chang was the beginning of the end of the Church in Shanghai. In the 1950s, the communists broke up the Legion of Mary and the Marian sodalities, forcing some of its members to "confess" that these organizations were "reactionary." Leaders and members who remained faithful were imprisoned or shipped off to distant labor camps.

In 1951, Archbishop Anthony Riberi, the papal nuncio to China, was expelled from the country. By 1952, almost all foreign missionaries were forced out of the country — among the exceptions was Bishop James Walsh, a Maryknoll Father who was accused of spying for the United States and sentenced to 20 years in prison (he was released in 1970).

On Sept. 8, 1955, the feast of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Bishop Kung and 1,200 Shanghai Catholics were arrested. After five years of detention, Bishop Kung was tried with 13 priests as a "traitorous counterrevolutionary clique." All 14 were convicted of counterrevolutionary thoughts and actions, and all were given prison sentences: Bishop Kung was sentenced to life in prison. He was released 28 years later and brought to the United States, to Stamford, Conn., where he lived with his nephew, Joseph Kung, until his death in 2000. In 1979, Blessed Pope John Paul II had secretly made Bishop Kung a cardinal; in 1991, he traveled to Rome, where the Holy Father presented him with his red hat.

By 1960, every Catholic institution and every Catholic church in Shanghai had been expropriated by the communists. Catholics — clergy, religious and laity — who would not renounce their allegiance to the Pope were imprisoned or sent to labor camps. A vestige of Catholicism was permitted to survive, temporarily, as the Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association, a "church" under the direct control of the government. But during the madness and violence of the Cultural Revolution, even membership in the Patriotic Association was considered counterrevolutionary: Louis Zhang Jiashu, who had been appointed "bishop" of Shanghai by the government, was forced by Red Guards — according to some accounts — to trample on a cross and shout, "Down with God!"

After the death of Mao, Chinese Catholics formed into two churches — the revived Patriotic Association and the underground Church loyal to the Holy Father. Each group has at least several million members, although the actual situation between the churches is not as straightforward as it appears on paper.

As Father Mariani explained in a recent phone conversation, many of the bishops who belong to the Patriotic Association have been reconciled with Rome, and there are Patriotic Association Catholics who are secretly loyal to the Holy Father, although it is impossible to estimate the number of these clandestine faithful.

The government's attack on the Catholic Church in China "was systematic and sophisticated," Father Mariani said. He went on to say, "The Church also developed its own systematic and sophisticated plan to ensure its survival. For six long years, the regime launched withering attacks on the Church. Yet the Church survived."