NEWS REPORT

from London Sunday Times

![]()

Priest's Murder Jolts Underground Mission

China Crushes the Church

by Michael Sheridan, Hong Kong

London Sunday News, July 11, 1999

© July 11, 1999 The London Sunday Times. Except for one-time personal use, no part of the following London Sunday Tinmes News material may be reproduced by an mechanical, photographic, or electronic process, nor may it be stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or otherwise copied for public or private use without written permission of the London Sunday Times.

HONG KONG, July 11 - (London Sunday Times) - When Father Yan Weiping, a priest from provincial China, made his way to Beijing to celebrate holy mass in secret for a congregation of believers, he may have expected harsh treatment by the authorities if he was caught. But he could hardly have known that he was to become a martyr for the Roman Catholic Church.

At 33, Yan was no ordinary cleric, but an ardent member of the world's largest underground church. It is comprised of an estimated 10m Chinese who remain loyal to Pope John Paul II - and shun the Chinese government's officially approved "Catholic Patriotic Association", which counts 4m registered adherents but is not recognized by the Vatican.

On May 13, however, Yan's mission came to a grotesque and violent end. According to the Cardinal Kung Foundation, a respected church group that monitors the plight of Chinese Catholics, he was saying mass at a private home in Beijing when the security forces burst in.

The priest was dragged away before the eyes of his congregation. That evening his battered body was found on a street in the capital. There was no post-mortem examination, but he appeared to have been beaten to death and thrown out of a window. His congregation believes he was murdered by the security police. There was no suggestion that Yan was in ill-health and Catholics regard suicide as a mortal sin. There has been no official comment.

The priest's death has sent a tremor through Christian communities in China, who face a new campaign against "superstition" aimed at combating cults and destroying any challenges to communist party authority.

According to diplomatic sources in Beijing, it has caused concern among a tiny group of western priests who are themselves living an underground existence in the Chinese capital and in towns. It is understood that the priests are from western Europe and the United States, working in China as teachers and experts without openly disclosing their vocation. Some priests, who are fluent in Mandarin Chinese, have been sent by Catholic religious orders in Hong Kong and Taiwan. There, the clergy watches the vast hinterland from which it was finally expelled by Chairman Mao in 1957, the year the "Patriotic Association" was set up by the regime.

They are not able to celebrate mass or administer the sacraments, except on rare occasions in foreigners' homes or on diplomatic premises protected by international law. Explaining their lonely mission, one priest, who lives in a university, has told a western envoy: "I bear silent witness"

In a sharpening climate of nationalist rhetoric, the danger of this calling has increased. "Local newspapers in China are full of the crackdown and admonitions to people not to become involved in cults," said Mickey Spiegel, a researcher on China at Human Rights Watch in New York. "Plus we have seen continued detentions of people who belong to the so-called underground Catholic church for years now."

The Cardinal Kung Foundation, which reported Yan's death, is regarded by Amnesty International and the State Department in Washington as a reliable source of scanty news about a church that has been persecuted for almost half a century. "It is difficult to get news from China," said Joseph Kung, of the foundation. "Getting what I have got required great effort from me and from the brave underground Catholic church community."

The foundation has also reported the arrest and torture of a seminarian from Yan's native Hebei province, near Beijing, where about half the country's Catholics live. It said Wang Qing was beaten, hung by his hands for three days and force-fed a filthy liquid that caused gastro-intestinal illness.

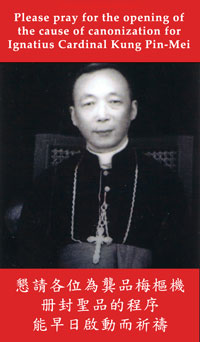

In another recent incident, four men caught attending a clandestine mass in Hebei province were sent to a labour camp, it said. The conflict between the Chinese state and the church has its incarnation in the awesome life story of Joseph Kung's uncle, the exiled 97-year-old Cardinal Ignatius Kung. Born in 1901 in Shanghai, the elder Kung became a priest and teacher, rising to the rank of bishop by the time revolution engulfed China.

Mao's secret policemen came for him in 1955 and kept him in prison for 30 years. In 1985 he was moved into house arrest and, in one of the most extraordinary encounters in church history, was produced at a carefully staged banquet to meet Cardinal Jaime Sin of the Philippines, who was visiting Beijing. Kung was not allowed to speak to Sin. Neither the visiting cardinal nor the Vatican knew whether the old man had kept the faith. But Sin shrewdly suggested that all present take turns to sing a song, and when Kung's turn came he sang out the Latin words that have saluted every Pope since Peter: "Tu es Petrus et super hanc petram aedificabo Ecclesiam meam" (You are Peter and upon this rock I will build my church). It was a profession of uncompromising loyalty. The Pope - who had secretly named Kung a cardinal in 1979 - later said that "the great majority of Chinese Catholics, precisely in order to live this fidelity in fullness, have chosen the path of suffering and silence".

The pontiff was able to greet Kung at the Vatican after the Chinese government allowed him to leave the country for medical treatment in 1987. But the cardinal cannot return home because his passport has been confiscated by Chinese diplomats. He remains in exile in Connecticut.

Yan, who was secretly ordained in 1988, was one of the most zealous guardians of the Kung legacy and had served six months in detention in 1990. Although the Chinese constitution provides for freedom of religious belief, Beijing cannot tolerate the notion that Catholic bishops should be nominated by the Pope.

Hints of compromise have proliferated. Some clergy in the "official" church have been quietly recognised by Rome. But factions and rivalries bedevil both the persecuted church and its opponent, hindering a solution.

Curiously, the next test of wills between the church and Beijing may come in Hong Kong, where many top officials are Catholics and the local clergy has become unusually outspoken in defence of democracy and human rights.

Cardinal John Wu, 74, recently drew widespread support from other churches for an open letter criticising the Hong Kong government's refusal to grant the right of abode to children born in China of Hong Kong citizens.

His designated successor, Bishop Joseph Zen, has been even bolder. "My belief," the bishop said in a speech in Rome, "is that providence has disposed that Hong Kong be again a part of China, just to show China the real way to true progress, democracy and respect for man."

It is a gospel the late Father Yan would have been more than happy to carry to Beijing.